Ever wondered how chickens actually reproduce? It’s a fascinating process that’s quite different from how mammals reproduce. While it may seem simple on the surface, chicken reproduction involves unique anatomy, efficient biology, and some clever natural adaptations.

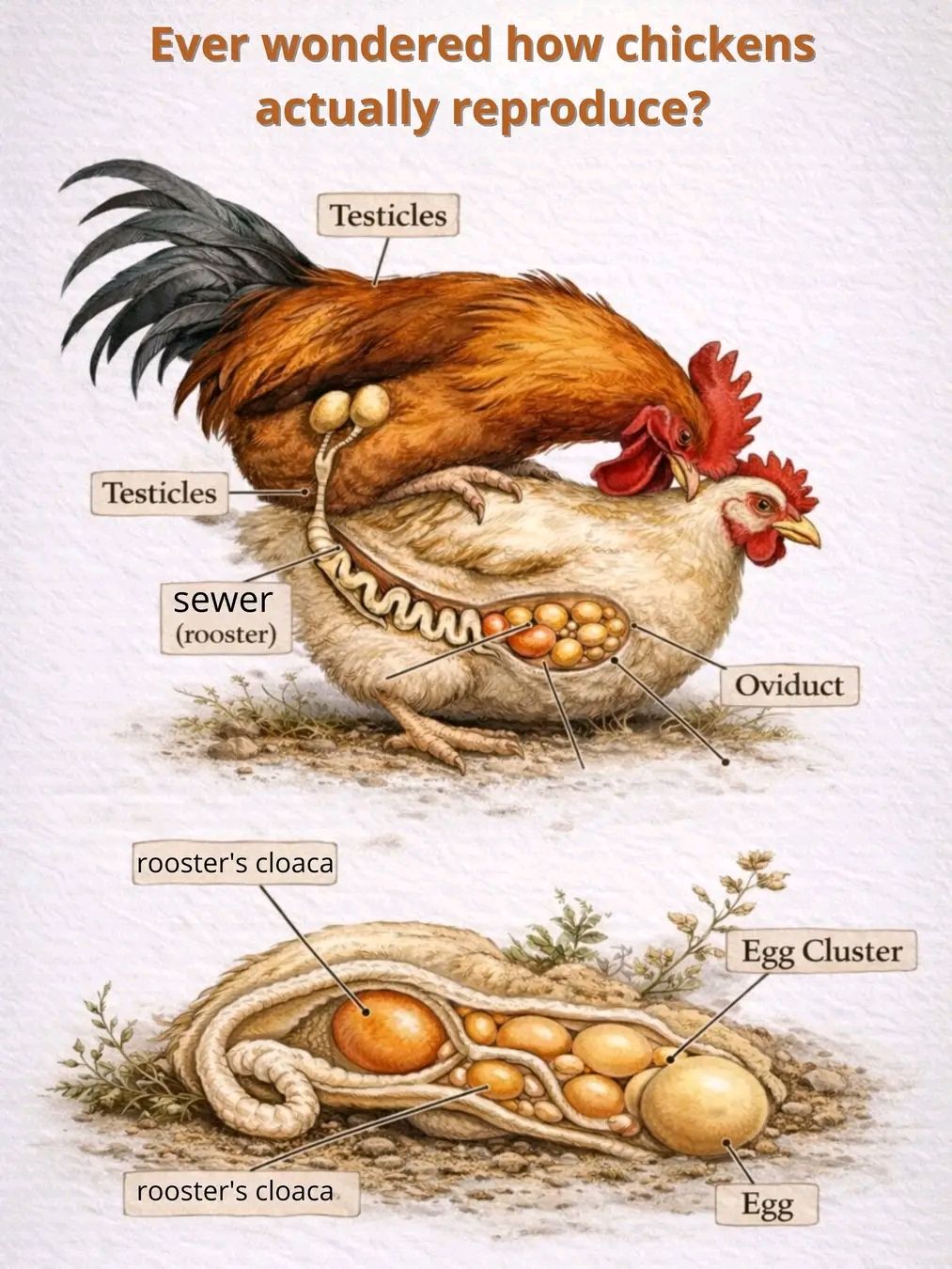

Unlike mammals, chickens do not have external reproductive organs. Both roosters (male chickens) and hens (female chickens) have a single opening called a cloaca. The cloaca serves multiple purposes: it is used for reproduction, waste elimination, and egg-laying. Because of this shared opening, chicken mating works very differently than what most people expect.

When a rooster mates with a hen, the process is quick and brief. The rooster mounts the hen, balancing himself with his feet and wings. During this moment, the hen lifts her tail slightly, allowing their cloacas to touch. This contact is known as the “cloacal kiss.” Despite the name, it is not romantic—it’s purely functional. Through this brief contact, the rooster transfers sperm into the hen’s reproductive tract. The entire process usually lasts only a few seconds.

One of the most impressive aspects of chicken reproduction is the hen’s ability to store sperm. After mating, a hen can keep sperm alive inside her body for several days, sometimes even up to two weeks. This means that a single mating session can fertilize multiple eggs over time. Each time the hen produces an egg during this period, it may already be fertilized without the rooster needing to mate again.

Egg formation in hens is a daily process. A hen’s ovary releases a yolk, which then travels through the oviduct. If sperm is present, fertilization occurs very early in this journey. As the yolk moves along, layers of egg white (albumen), membranes, and finally the hard shell are added. This entire process takes about 24 to 26 hours, which is why many hens lay roughly one egg per day.

A common misconception is that hens need a rooster in order to lay eggs. In reality, hens lay eggs whether or not a rooster is present. These unfertilized eggs are the same eggs people commonly eat. However, without fertilization, these eggs can never develop into chicks. Only eggs laid by hens that have mated with a rooster have the potential to become baby chickens.

If a fertilized egg is kept warm—either naturally under a broody hen or artificially in an incubator—it can develop into a chick. Incubation usually takes about 21 days. During this time, the embryo grows rapidly, forming organs, feathers, and bones. Near the end of incubation, the chick uses a special “egg tooth” to break through the shell and hatch.

Nature has made chicken reproduction incredibly efficient. The quick mating process reduces vulnerability to predators, while sperm storage allows hens to produce fertilized eggs without constant mating. This system helps ensure the survival of the species, even in environments where conditions are unpredictable.

In the end, chicken reproduction may be simple, fast, and somewhat surprising—but it’s also a brilliant example of how nature adapts biology for maximum efficiency. From the cloacal kiss to daily egg production, chickens prove that even the most ordinary farm animals have extraordinary life processes happening behind the scenes.