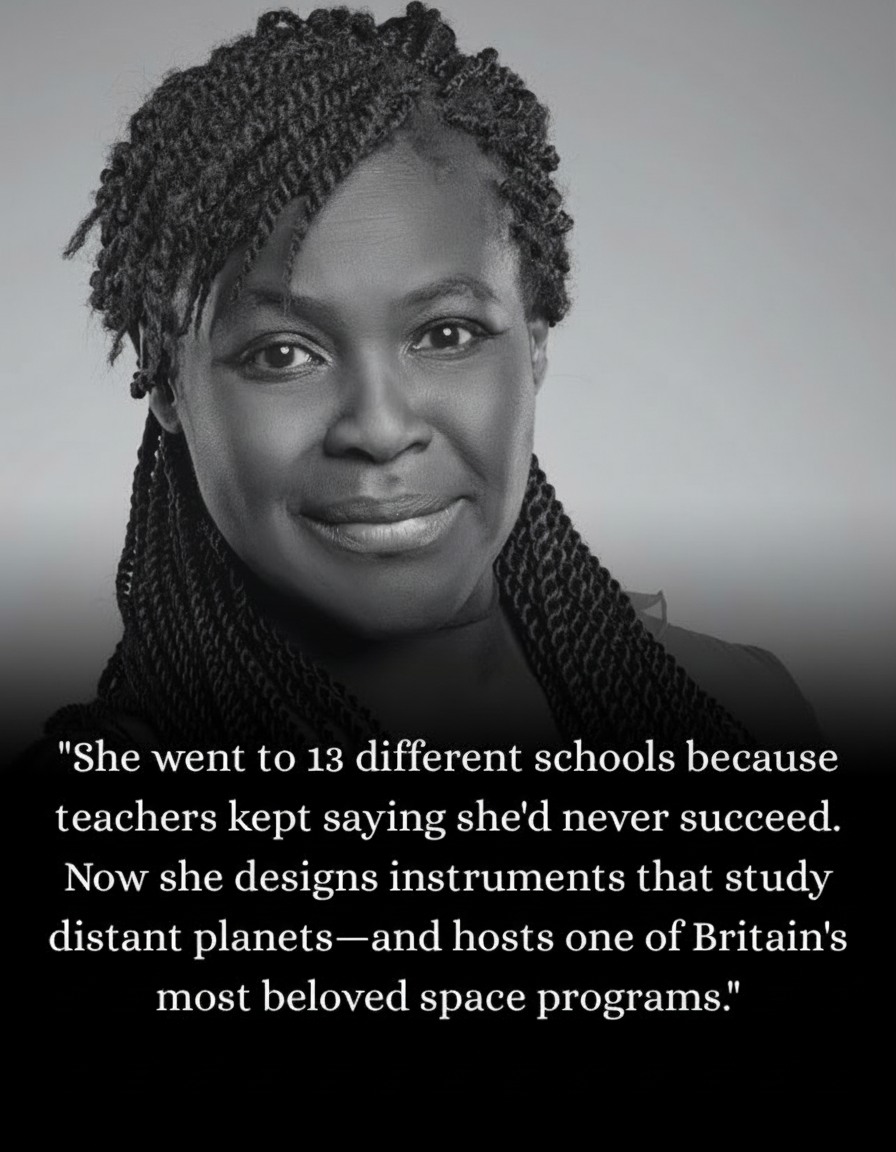

“She went to 13 different schools because teachers kept saying she’d never succeed. Now she designs instruments that study distant planets—and hosts one of Britain’s most beloved space programs.

As a child, Maggie Aderin-Pocock was told she would never excel because of dyslexia. Reading was hard. Words moved on the page, rearranging themselves before she could catch their meaning. Teachers underestimated her. Some suggested she lower her expectations.

But dreaming wasn’t hard at all.

At night, she would stare through her bedroom window in London, imagining spacecraft gliding through the dark. She would watch the stars and wonder what it would be like to touch them, to build the machines that could reach them.

Born to Nigerian parents who had immigrated to Britain, Maggie carried that curiosity everywhere. She built model rockets from cardboard and paper. She stayed late in science labs at school, the one place where her mind felt at home. She refused to shrink her ambition to match other people’s limited expectations.

School was a constant struggle—not just academically, but socially. Between ages 4 and 18, Maggie attended 13 different schools as her family moved around London. She was often the only Black student in her classes. She had dyslexia in an era when learning differences were poorly understood. Many teachers saw her struggles with reading and assumed she couldn’t succeed in science.

They were spectacularly wrong.

Maggie found her strength in patterns and pictures, in the way science made invisible things visible. Her mind worked differently, and that difference became her advantage. While other students excelled at memorizing text, she excelled at visualizing complex systems—how machines moved, how light bent, how orbits worked.

“”I see things in 3D in my head,”” she later explained. “”I can rotate objects, take them apart, see how they work. Dyslexia made reading harder, but it made spatial thinking easier.””

She pursued physics and eventually earned a PhD in Mechanical Engineering from Imperial College London in 1994, focusing on mechanical engineering and instrumentation. Her doctoral research involved developing new technology for spacecraft instruments.

Then she did what she’d dreamed about as a child: she helped design instruments that study the stars.

Maggie worked on cutting-edge space instrumentation for over two decades. She contributed to satellite projects studying Earth’s atmosphere and climate. She helped develop instruments for the Gemini Observatory in Chile, telescopes that peer deep into space searching for exoplanets—worlds orbiting distant stars.

She became a space scientist specializing in optical instrumentation, developing technology that allows us to see what the naked eye cannot: the composition of distant atmospheres, the temperature of faraway worlds, the fingerprints of alien atmospheres.

But her most important work might be what she did next.

Dr. Maggie Aderin-Pocock decided that the wonder she felt as a child—staring at stars through her bedroom window—should belong to every child, especially those who, like her, struggled in traditional classrooms.

She became one of Britain’s most beloved science communicators. In 2014, she became the co-presenter of BBC’s “”The Sky at Night,”” the world’s longest-running astronomy television program, originally hosted by Patrick Moore since 1957. She was the first woman to regularly present the show in its nearly 60-year history.

Her energy and warmth drew children to astronomy the way gravity pulls planets into orbit. She didn’t just explain the science—she made it feel accessible, exciting, magical. She spoke in ways that made complex ideas clear, using her own visual thinking strengths to help others see what she saw.

She visited schools across Britain, especially those in underserved communities, bringing telescopes and wonder. She told children with dyslexia and other learning differences that their brains weren’t broken—they were just wired for different kinds of brilliance.

“”I want to get more girls interested in science,”” she said in interviews. “”I want to get more people from ethnic minorities interested. I want to show that science is for everyone, not just a particular type of person.””

In 2009, she was awarded an MBE (Member of the Order of the British Empire) for her services to science education. In 2020, she received an honorary doctorate from several universities recognizing her contributions to science communication.

She created a program called “”Science Innovation”” that brings hands-on science experiences to schools, particularly targeting girls and minority students who might not see themselves reflected in traditional science careers.

Dr. Maggie Aderin-Pocock proved that science is not just equations and telescopes. It is imagination, empathy, and persistence. She proved that there is no single way to learn, no single way to think, no single way to shine.

She reminds the world that the people told they can’t succeed are often the ones who change everything—because they have to fight harder, think differently, and refuse to accept limits others place on them.

Every time she speaks about the sky, she makes it feel closer—as if the universe itself is listening back. And in a way, it is. Because the girl who couldn’t read well is now one of the people helping humanity read the stars, decipher the composition of distant worlds, and imagine what lies beyond.

She went to 13 schools where teachers doubted her. Now she teaches the world to look up”

From Dyslexia to the Stars: The Journey of Dr. Maggie Aderin-Pocock